What is Barth Tired? A Qualitative Approach to Understanding Fatigue in Barth Syndrome from the Perspective of Family Members

Stacey Reynolds*, Emma Daw, Isabelle Babson and Virginia Way Tong Chu

Department of Occupational Therapy, Virginia Commonwealth University, Virginia, US

- *Corresponding Author:

- Stacey Reynolds

Department of Occupational Therapy, Virginia Commonwealth University, Virginia, US

E-mail: Reynoldsse3@vcu.edu

Received date: July 26, 2022, Manuscript No. IPRDDT-22-14245; Editor assigned date: July 28, 2022, PreQC No. IPRDDT-22-14245 (PQ); Reviewed date: Aug 10, 2022, QC No. IPRDDT-22-14245; Revised date: Aug 17, 2022, Manuscript No. IPRDDT-22-14245 (R); Published date: Aug 26, 2022, DOI: 10.36648/2380-7245.8.8.72

Citation: Reynolds S, Daw E, Babson I, Chu VWT (2022) What is Barth Tired? A Qualitative Approach to Understanding Fatigue in Barth Syndrome from the Perspective of Family Members. J Rare Disord Diagn Ther Vol. 8 No.8:72

Abstract

Context: Barth Syndrome (BTHS) is a rare x-linked, recessive, genetic condition linked to mutations in the TAZ gene. Fatigue in both cardiac and skeletal muscles is a common symptom for individuals with BTHS; however, research on fatigue specifically in the BTHS population is limited.

Objective: The purpose of this study was to understand how families and caregivers of individuals with BTHS perceive the impact of fatigue on the engagement and daily life functioning of the individual and the family unit.

Design: We used a qualitative phenomenological approach. Semi-structured interviews were completed via the zoom platform with individuals or family units. Atlas ti. software was used to code each interview transcript, and data inquiry features were used to identify connections and themes. Member checking was completed to validate themes.

Subjects: Twenty-three family members representing seventeen individuals with Barth syndrome.

Setting: Virtual

Results: Five primary themes were extracted through an inductive process: 1) Barth fatigue does not always stop families from doing important things, but extra planning/ modification is needed; 2) The worse the fatigue, the greater the impact on the individual and the family; 3) There are physical and non-physical signs of BTHS; 4) Barth individuals look “normal”, so families/individuals are sometimes misunderstood; 5) There is a transition that occurs from parents managing their child’s fatigue, to the affected individual learning their own strategies or selfregulation.

Conclusion: These findings give valuable insights into what “Barth Tired” really means from the perspective of families of affected individuals.

Keywords: Barth Syndrome; Fatigue; Mitochondria; Genetic Disorder; Qualitative Phenomenology.

Introduction

Fatigue is a common characteristic in many mitochondrial disorders that have either a neuromuscular and/or a cardiovascular involvement [1]. This fatigue may be perceived fatigue, presented as low energy, exhaustion, or tiredness, or physiological fatigue, presented as exercise intolerance. Research has shown that 70-100% of persons with primary mitochondrial diseases report at least moderate fatigue [1-3] while preliminary data in some populations suggests a correlation between disease severity and fatigue severity [2,4]. Presence of symptoms and severity of fatigue may also correlate with rates and severity of mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety, as well as sleep issues in persons with primary mitochondrial diseases. Importantly, research on persons with primary mitochondrial diseases has implicated fatigue as having a role in an individual’s ability to complete daily life skills such as personal hygiene, swallowing, and toileting [1,5]. Collectively, fatigue can impact all aspects of a person’s life and manifest both physically and mentally, in ways that impact overall quality of life [6]. One of the many mitochondrial disorders causing these impacts is Barth Syndrome (BTHS). This study was part of a larger effort to understand how fatigue manifests in BTHS and the impact on quality of life. The purpose of this specific study was to understand how families and caregivers of individuals with BTHS perceive the impact of fatigue on the engagement and daily life functioning of the individual and the family unit.

Background

Barth syndrome is a rare x-linked, recessive, genetic condition linked to mutations in the TAZ gene, the gene which provides instruction for the coding of the protein Tafazzin [7,8]. Tafazzin works in the mitochondria to alter cardiolipin, a lipid that functions to meet energy demands and transport proteins within the cell. With the TAZ gene mutated, the cardiolipin cannot be altered correctly and thus cannot perform its necessary functions, which impairs normal mitochondrial function to meet energy demands. Secondarily, the tissues that make up the most important and hard-working muscles like the heart and lungs are most susceptible to mutation and cell death.

As a result, fatigue in both cardiac and skeletal muscles is a common symptom for individuals with BTHS; however, research on fatigue specifically in the BTHS population is limited.

Of the studies that have been done, the focus has primarily been on the physiological aspect of fatigue (i.e., exercise tolerance or endurance) [9-11]. Collectively, this line of research has established that altered cardiac and skeletal muscle bioenergetics and impairments, secondary to mitochondrial defects, are directly correlated with decreased exercise capacity in adolescents and young adults with BTHS.

While exercise intolerance is an essential feature of fatigue that needs to be understood in BTHS, fatigue is known to be a much broader construct. Fatigue experienced by individuals with BTHS extends well beyond the exertion required to perform the 6-Minute Walk Test (6MWT) and Sit-to-Stand Test (SST), which have been the most commonly used assessments of physical endurance within the BTHS population [12,13]. Individuals with BTHS are known to have higher rates of perceived tiredness, mental fatigue, sleep problems, and psychosocial concerns like anxiety and depression; all symptoms that have been linked to fatigue in other mitochondrial disorders [14-17]. Unsurprisingly, health-related quality of life has been found to be diminished in the BTHS population, particularly in areas of physical and school functioning [6]. Research is needed that expands on the prior conceptualization of physiological fatigue to examine the multidimensional aspects of fatigue and its impact on daily living in natural environments.

Study purpose

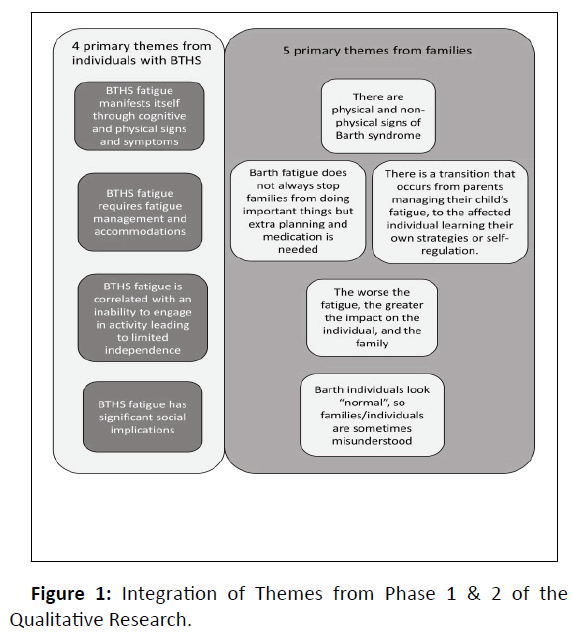

To address this need, our team designed a mixed methods study to 1) better understand what fatigue means to the BTHS community, and 2) explore ways to quantitatively measure fatigue as a holistic construct. We previously published our results from interviews conducted with BTHS-affected individuals. In the first phase of the study, we found that BTHS fatigue 1) has significant social implications for individuals, 2) manifests itself through cognitive and physical signs and symptoms, 3) is correlated with an inability to engage in activity leading to limited independence, and 4) requires fatigue management and accommodations [18]. This paper reports on the second phase of the study, the purpose of which was to understand the impact of BTHS fatigue on individuals and family units from the perspective of family members and caregivers. Our guiding research question for this study was, from the perspective of family members or caregivers, how does the fatigue experienced in individuals with BTHS affect engagement and functions in daily life?

Methods

Research design

All research activities, including consent and assent procedures, were approved by the sponsoring university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB, Study Number HM20021612). We chose a qualitative phenomenological approach to answering our research question, since the focus was to understand how families and caregivers experienced BTHSrelated fatigue within the family unit. Data collection was achieved through interviews and focus groups with family members using the Zoom video conferencing platform (Zoom Video Communications Inc.).

Sample

Participation was open to parents, siblings, grandparents, and other individuals aged 12 or older with a close relationship to an individual with Barth syndrome. There were no geographic restrictions for participation since interviews were conducted virtually, however, participants had to be able to understand and converse in English. Multiple members of the same family were eligible to participate.

A purposive, convenience sampling method was used to recruit participants. Informational flyers were sent via the Barth Syndrome Foundation (BSF) listserv as well as posted on the BSF website. A roundtable discussion about fatigue and the research project was also sponsored by the BSF; attendance was free and voluntary, and a recording of the roundtable discussion was posted to the BSF website. Interested parties were able to contact researchers directly via email to express interest in participating and to schedule an interview. Data collection occurred over a period of ~12 weeks until no new themes were emerging from the data (i.e., data saturation was reached).

The final sample included twenty-three individuals representing seventeen different BTHS-affected individuals ages 5 years through mid-adulthood (exact age redacted for confidentiality due to limited number of adults this age living with BTHS). Participants included one sibling, three parent dyads (both parents together), twelve mothers, and one family group (two parents and two grandparents). All participants were over the age of 18 and provided written consent via Docusign software. The Docusign system utilizes Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) 256-bit encryption, and MFA to ensure online authorized persons have access to information stored on their secure cloud. All completed consent/assent documents were stored in secured research team cloud folders.

Data acquisition

The Zoom video conferencing platform was used for collecting data. It is a secure network offering Advanced Encryption Standard 256 using one-time keys for specific sessions. There is also end-to-end encryption between members of the session in which no third party (including Zoom) can access the meeting, content, or data post session closing. Entry to meetings was warranted through specific keys generated for individual meetings and was protected by passwords for entry. Audio recordings from the zoom recording feature were utilized, and download was secure and encrypted, and stored on team member devices. The files were stored in password protected files on the researcher’s device until transferred to REV.com (Rev.com San Francisco©) for transcription. Once transcripts were securely transferred back to the researcher, identifiers were removed and transcripts were stored on a passwordprotected device.

Interviews

Seventeen semi-structured interviews and family focus groups were conducted following a script developed by our research team (Table 1). Each interview included seven open-ended questions. Each of the first six questions have two to four possible probes to be used as needed to stimulate further discussion. Interviews were conducted by a trained doctoral student under the supervision and guidance of a senior researcher.

| Question | Possible Follow Up Questions/Probes |

|---|---|

| When I say the word “fatigue” in relation to Barth syndrome, what are the first words or images that come to your mind? | • Does fatigue mean something different than tired? |

| • What are you seeing in your mind’s eye right now? | |

| • Are there any other words that you are thinking of? | |

| When do you notice fatigue in your child with BTHS? | • Related to specific activities? |

| • Related to time of day? | |

| • Do you think you could tell they were tired before they knew they were tired? | |

| How has fatigue influenced your child’s ability to do things that are important to them? | • Work/play/leisure? |

| • Social? | |

| • Self-care? | |

| How has fatigue influenced your family’s ability to do things that are important to you? | • Day-to-day activities (meals, sleep, extracurricular activities, school/work) |

| • Special events/vacation choices | |

| • Impact on self/siblings | |

| How has your child’s fatigue influenced your relationship with others? | • Do you ever say no to social or family events and activities because your child is too tired? |

| • Do you ever think people are upset with you because you couldn’t do something with them or for them? | |

| What do you do when you see your child is fatigued? | • Do you tell them to rest? |

| • Do you encourage them to keep going? | |

| • Do you suggest snacks/drinks? | |

| What else do you think people should know about fatigue or tiredness in Barth syndrome? |

Table 1: Interview Questions and Probes.

Data analysis

Deidentified interview transcriptions were checked for accuracy against the original audio files then imported into ATLAS.ti, a qualitative research software program (Scientific Software Development GmbH). The reviewed transcripts were then read and re-read by two team members (ED, IB). The primary research assistant (ED), who conducted the interviews, also met weekly with the study primary investigator (SR) to discuss emerging trends in the data and to review her reflexivity log. The analysis procedures occurred in an iterative fashion where we interviewed, analyzed, discussed, and repeated the process until data saturation was reached.

A preliminary code sheet was developed, and two researchers (IB and ED) selected a sample of five transcripts then coded each of the transcripts individually to develop interrater agreeance. Upon coding completion of the sample of five transcript documents the interrater agreement was calculated to be 81.5%. Following coding of the initial five interviews, the research team met again to discuss findings and refine the coding frames. Each of the refined codes was selected to be a part of the final coding framework (Table 2). Using the agreed upon coding framework IB and ED coded all transcripts using the ATLAS.ti platform and created memos within the software program to begin identifying key themes.

| Code | Operational Definition |

|---|---|

| Social Impact | Instances where the affected individual and/or family member were unable to participate in a social event/outing due to fatigue. |

| Impact of Fatigue on Family Function | Statements which indicate that family routines, habits, or roles are impacted by the affected individual’s fatigue. The net effect of any aspect of fatigue on the individual’s family or individual family members |

| Family Response(s) to Fatigue | Things the family member would do, or observe the individual do, when fatigue set in. |

| Limited Independence and Experience | Related to the inability of the affected individual to do or engage in a desired activity, task, or relationship due to fatigue. |

| What Barth Tired Means | Describing any aspect of BTHS that insights feeling of tiredness or fatigue. Also, may include comparisons of what the caregiver experiences physically, mentally or emotionally compared to fatigue observed in the affected individual. |

| Triggers | Things that increase or stimulate fatigue in the affected individual. May be things that the family avoids to prevent fatigue (e.g., heat). |

| Planning | The action or process of making a plan or arrangements related to the expectation of ensuing BTHS-fatigue in the affected individual. |

| Family Stress | Anxiety, tension, grief or nervousness described by family members of affected individuals. |

| Impact of Fatigue on School Functioning | Statements related to educational or academic impact of BTHS-fatigue on the individual, or how the family members interacted on behalf of the individual in the school setting. |

| Emotional Impact on the Individual | The net effect of any aspect of BTHS fatigue on the individuals emotional state including mood and feelings |

| Development of self-awareness | Statements where the caregivers describe the affected-individual developing an understanding of their own fatigue, limitations, and self-management of symptoms. |

| Mental Impact on the Individual | The net effect of any aspect of BTHS fatigue on the individual’s mental state |

| Energy-conservation & Accommodations | Description of physical actions taken specifically to conserve energy OR pre-planned arrangements or agreements made to prevent or reduce fatigue. |

| Invisible Disability | Statements where family members refer to the affected individual looking “normal” or stigma experience because others could not “see” something wrong with their child/grandchild/sibling. |

Table 2: Code Directory.

BTHS = Barth syndrome

Preliminary themes were then shared with the primary investigator, and member checking was conducted with a random sample of five participants. Based on participant feedback, one theme was refined, rechecked with the participants for agreement, and then finalized.

Results

Inductive thematic analysis led to the extraction of five primary themes:

• Barth individuals look “normal”, so families/individuals are sometimes misunderstood

• The worse the fatigue, the greater the impact on the individual and the family

• There are physical and non-physical signs of Barth syndrome

• Barth fatigue does not always stop families from doing important things, but extra planning and modification is needed…which can be exhausting

• There is a transition that occurs from parents managing their child’s fatigue, to the affected individual learning their own strategies or self-regulation.

Barth individuals look “normal”, so families/ individuals are sometimes misunderstood

Ten out of the seventeen transcripts reviewed referred to Barth in some way as a hidden disability and/or discussed stigma they experienced when others did not understand their child’s disorder. Parents in particular talked about the looks they would get when their child “who looks normal” wouldn’t eat, would need their bags carried for them, or actually need carried (or to ride in a stroller past a certain age). One mother noted “So…I had friends who just didn't get it, you know, like, they'd say, well, if he gets hungry, he'll eat. No, he really, he wouldn't, he wouldn't eat. They felt that my kids were manipulating me, because they looked, you know, they looked normal”. One father noted, “And I would have people come up to me and say, he's too big to be carried, put him down, let him walk, you know, and you just want to…but you have to let that go because people don't know and it's really hard. And it, it really does affect the whole family”.

Family members also noted that affected individuals were often labeled as lazy or underachieving (e.g., in school) because teachers or even relatives did not understand that they just could not do it. As noted by one family, “Before his diagnosis [siblings] would call him lazy…and they didn't know, now they feel terrible about it, but that's what happens to our kids. It happens at school, at home, relatives, you know, relatives say it, you know, get up, come on, and go run around”. Another parent summarized this by stating, “It is progressive and it is debilitating, but it's also invisible. You know, it's like, if you vomit people see you're sick. Right? If you vomit, there is a manifestation, you can see it happen. And if you have a cut, people can see a wound, but they can't see fatigue”.

There are physical and non-physical signs of Barth Syndrome

All of the participants we interviewed endorsed that their affected family member experienced physical fatigue as evidenced by the need to take a break, slow down, or “just stop” all physical activity. One parent noted that “it’s not something he can just push through”. Sometimes fatigue was accompanied by physical pain as well. Sixteen of the seventeen interviews also described signs of emotional fatigue, behaviors such as listlessness, meltdowns, crying, and frustration particularly in children and adolescents. One parent recounted their child’s response during a soccer match stating “he'll just stop or he'll just stand still, or he'll start getting upset and crying. And he did this one time at soccer this year and the coach was like, oh my God, are you okay? And he just said, I’m tired. This is what happens when I’m tired”. Another parent described the emotional fatigue as “they would get mean them, their attitude… I mean their people skills would get worn out.”

Participants also described signs of mental fatigue that they observed in the affected individual, symptoms like difficulty focusing or sustaining attention at school or even during activities they enjoy. One family member noted, “He has a hard time focusing and he just, he gives up really easily because of the mental fatigue... And I don't think people think of that when they think of fatigue”. The educational impact of fatigue also went beyond the classroom into afterschool activities as well. As noted by one parent “He can’t take classes he wants to take, he has to take the core classes to get through school. Then he can’t do afterschool things because he’s tired by the end of the day”. The combined impact of mental and emotional fatigue was summarized by one family member who stated, “by the end of the school day he would have some behavioral issues, and an inability to complete work, and all I think, because he just was too tired to hold it together”.

The worse the fatigue, the greater the impact on the individual and the family

While a quantitative analysis was not within the scope of this study, our team identified a trend in the data suggesting that when fatigue symptoms were milder, the impact on independence and quality of life was less. Conversely when fatigue symptoms were moderate to severe (either within the individual, or on a specific day) families described how it became almost impossible for the affected individual to go to work, do homework, take a shower, play with friends or siblings, or even walk up the stairs at the end of the day. One parent noted of their affected adolescent, “it goes to something as simple as hygiene, feelings like you have enough energy to get through a hot shower and then do I have enough energy to brush my teeth and put deodorant on? I've literally brought deodorant to him and there's times where he just doesn't want to wear it. But I think when you're so fatigued, after you do a task, it's hard to do the next task and the next task.” Another parent noted, “You know, one of the things he likes to do is cooking, but when you're exhausted, you don't have the energy to stand around and cook”.

Not being able to work was a topic discussed by many of our participants whose family member was over the age of 18 years. One family member noted “it really does make a big difference in a lot of ways with relationships, with quality of life. I mean, he would be able to work if he wasn't so fatigued…the stigma that goes with not working. I think that there's also probably a bit of shame about”.

Fatigue levels not only impacted the independence and quality of life of the affected individuals, but spilled over to the larger family unit as well. One parent noted, “I think his life would be very, very different and all of our lives would be different as a result because I think he would be able to do more”. Another parent summarized this theme with the following statement:

The fatigue is kind of like an unforeseen illness that not that many people are aware of. And it’s one thing that's really hard to grasp, what it does to somebody and the amount of…joy of life, quality of life, that it robs him of is astounding. We put the positive spin. We don't ever want him to feel that burden, but I will tell you that when they talk about caregiver burden, which is what I do with a lot of my work, it's definitely there. And it's family burden. It's a burden amongst our extended family… [And the] burden on [SON], is huge.

Barth fatigue does not always stop families from doing important things, but extra planning and modification is needed…which can be exhausting

This theme was initially phrased “Barth fatigue does not stop families from doing important things but extra planning or modification is needed...which can be exhausting”. However, after our first phase of member checking with participants the word always was added as a caveat to the statement. This was because after some reflection families noted that Barth-related fatigue does sometimes stop families from doing things, or there are activities they wouldn’t even consider doing because fatigue is a factor.

Throughout the interviews participants frequently (78 coded statements) discussed the extra effort related to travel or social outings; we heard about extra planning related to parking, stroller access, how many trips to the car, how families would transport medication, where the nearest surgical/medical centers were located, accessibility of rental homes or hotels, and just planning out how many activities could be done in a day before fatigue would ultimately set in. One mother stated, “We can do it. We just have to figure out how, and that's where in part my exhaustion comes from is trying to figure out all the extras that we need to make something happen and make it fun”. This idea that the extra planning can be draining for families was confirmed by another parent who stated:

I'm sure there is a way, but it exhausts me thinking of, oh my gosh, how would we ever begin to do that? Who's going to carry him. Who's going to pull him. Who's going to make sure his battery is charged out in the middle of nowhere…there's just so much to be involved in accommodated for. You have to really work yourself up to it sometimes so that it works out for your family, but it takes a lot to do that. It's not like normal planning for vacations or for a picnic.

Despite the extra effort, however, families repeatedly noted that participating in family activities or vacations were possible and that they tried not to let BTHS or Barth-related fatigue be a barrier. As noted by one parent, “accommodations can make it happen no matter what we're going to do. I definitely don't let the Barth tired hinder us or stop us”.

There is a transition that occurs from parents managing their child’s fatigue, to the affected individual learning their own strategies or selfregulation

While reviewing interview transcripts, our team identified another trend in which parents of younger children with Barth were more vigilant (“helicopter-like”) and watched for signs of their child’s fatigue so that they could intervene when they thought that things were going downhill. One parent described watching their child playing tag with friends and having to tell him, “Ok, well you’ve face-planted twice on the cement; I think your body is telling you it’s time to stop playing”. Another family member recalled the balancing of more active days with more calm days noting, “I just feel like we're kind of mindful like, if we had a full day, that the next day needs to be a little bit more chill and it's not like he's in bed until noon. It just is a little bit slower, slower on his body, slower on his mind, cooler, and all those things to rest and recover.”

But we noted that when we talked to parents of adolescents, there was a transition where the affected individual was starting to be more aware, and realize how to manage themselves; one mom of an adolescent noted “And he's actually, he's starting to realize it too. So, he's he starting to catch it, but like everybody else, you don’t always, it takes years before you fully understand your, your body”. Another parent of an adolescent stated similarly, “I'll say to him, do you think that you might be feeling a little tired or that you might need to save some of that energy and then he'll think, and he'll be like, oh yeah, you know what this is hurting or my heart's beating so hard…so he's, he's definitely catching it.”

In contrast, parents of affected adults did not report having involvement in the day-to-day management of their child’s fatigue. Rather they noted that their affected family member had their own strategies for self-management, such as, “if he knows he has something coming up, he'll plan for it and rest. And he won't plan anything else a couple of days before the day of, or a few days after, because he'll have to sort of rest [then] do the thing and then recover. So that's very, um, standard for him.”

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to understand the impact of BTHS fatigue on individuals and family units from the perspective of family members and caregivers. To this end, we found five primary themes that suggest that fatigue manifesting as physical, mental, and emotional exhaustion could impact various aspects of family function and overall quality of life. These findings support prior correlational research published by Kim and colleagues [7] who found that the worse the fatigue (as measured by the PEDSQL), the greater the impact on healthrelated quality of life in BTHS. Our study extends these quantitative findings to suggest that features such as social isolation, stigma, and limited energy for work, leisure, and educational tasks may be particularly impactful areas for both affected individuals and their families. It also highlighted the extra planning, modifications, and accommodations that families must make, or at least consider, due to the intense and pervasive nature of BTHS-fatigue.

Our findings also align with themes identified in phase one of our study in which we interviewed affected individuals. That study represented the perspectives of 20 individuals with BTHS ranging in age from five years to adulthood (average age 20.9 years). Both studies identified that fatigue extends beyond physical exhaustion and includes mental (i.e., educational or cognitive) and emotional facets as well. We also saw similar trends in which high levels of fatigue resulted in less independence and a greater impact on the affected individual and the family. Both studies also indicated social implications and social stigma that comes with having BTHS and particularly Barth-related fatigue. Finally, family members and affected individuals both discussed the need for planning and accommodations in order to participate in meaningful activities; however, the burden of planning seems to shift from the parents to the affected-individual over time. Figure 1 presents these themes and their alignment.

Note: Themes presented on the left of this figure were published in the article by Babson and colleagues [18].

Information gained from this study can help to guide the selection of clinical trial outcome measures specific for BTHS encapsulating targets important not only to the individual, but caregivers as well. Future studies may also want to specifically explore the construct of caregiver burden within the BTHS population. While “burden” did not specifically come up in any of our interviews, some family members did express stress related to planning and accommodation, as well as worry or vigilance that was part of their daily lives. Research in other pediatric rare disorders such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy has found that caregiving can have a considerable impact on work life and productivity [19]. In a systematic review by Landfeldt and colleagues [19], parenting a child with a degenerative neuromuscular disorder such as Duchenne’s is frequently associated with impaired health-related quality of life for the caregiver as well as poor sleep quality, reduced family function, depression, pain, stress, sexual dysfunction, and/or lower self-esteem. While BTHS and Duchenne’s present very differently, they are both X-linked conditions that affect skeletal and heart muscle and include symptoms of fatigue and motor delays. Treatments aimed at improving the symptoms of BTHS, or restoring mitochondrial function through gene therapies, may also want to consider how these treatments impact caregiver burden and/or family function as well. In terms of clinical practice, these results serve as a resource for clinicians to better support families whose children are seeking medical or therapeutic care.

Limitations

It may be viewed as a limitation that our recruitment occurred primarily through the Barth Syndrome Foundation (BSF). There is a possibility that family members who are not connected with the foundation, or whose children have undiagnosed cases of BTHS, may have different experiences than those individuals who participated in this study. Similarly, our sample included only those individuals who could speak and comprehend conversational English. This limited our sample primarily to those living in North America, the United Kingdom, and Australia. It may be that families living in other geographic regions have different experiences than those represented in our sample and this should be a consideration for future studies.

Despite these challenges, this study employed many strategies to enhance qualitative rigor. Throughout the study, investigators ensured all needed documentation was established and maintained in an audit trail to support confirm ability of the study. Direct quotes representing meaningful theme description were used to establish transferability. All study procedures were followed and ensured with validating methods such as stored recordings and dual coding to enhance dependability. As such, this study provides important direction for future research with the ultimate goal improve quality of life for individuals with BTHS and their families.

Acknowledgment

The research team would like to thank Dr. Erik Lontok, scientific director of the Barth Syndrome Foundation (BSF), and Shelley Bowen, former chair of BSF and current director of Family Services and Advocacy, for their help with subject recruitment and study design. We would also like to thank the families who gave their time to this study. This research was supported by an Idea Grant from the Barth Syndrome Foundation (NIH R41) and the use of REDCap was made possible by award number UL1TR002649 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR).

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to declare.

References

- Gorman GS, Elson JL, Newman J, Payne B, McFarland R, et al. (2015) Perceived fatigue is highly prevalent and debilitating in patients with mitochondrial disease. Neuromuscul Disord 25: 563–566.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Parikh S, Galioto R, Lapin B,Haas R, Hirano M, et al. (2019) Fatigue in primary genetic mitochondrial disease: No rest for the weary. Neuromuscul Disord 29: 895–902.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Verhaak C, De Laat P, Koene S, Tibosch M, Rodenburg R, et al. (2016) Quality of life, fatigue and mental health in patients with the m.3243A > G mutation and its correlates with genetic characteristics and disease manifestation. Orphanet J Rare Dis 11: 1–8.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Smits BW, Fermont J, Delnooz CCS, Kalkman JS, Bleijenberg G, et al. (2011) Disease impact in chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia: More than meets the eye. Neuromuscul Disord 21: 272–278.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Codier E, Codier D (2014) Understanding mitochondrial disease and goals for its treatment. Br J Nurs 23: 254–258.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Kim AY, Vernon H, Manuel R, Almuqbil M, Hornby B, et al. (2022) Quality of life in Barth syndrome. Therap Adv Rare Dis 3: 1-20.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Clarke SLN, Bowron A, Gonzalez IL, Ecob RN, Clayton N, et al. (2013) Barth syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis 8: 23–28.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Taylor C, Rao ES, Pierre G, Chronopoulou E, Hornby B, et al. (2022) Clinical presentation and natural history of Barth Syndrome: An overview. J Inherit Metab Dis 45: 7–16.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Bashir A, Bohnert KL, Reeds DN, Peterson LR, Bittel AJ, et al. (2017) Impaired cardiac and skeletal muscle bioenergetics in children, adolescents, and young adults with Barth syndrome. Physiol Rep 5: p13130.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Spencer CT, Byrne BJ, Bryant RM, Margossian R, Maisenbacher M, et al. (2011) Impaired cardiac reserve and severely diminished skeletal muscle Oâ?? utilization mediate exercise intolerance in Barth syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: 2122-2129.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Cade WT, Bohnert KL, Peterson LR, Patterson PW, Bittel AJ, et al. (2019) Blunted fat oxidation upon submaximal exercise is partially compensated by enhanced glucose metabolism in children, adolescents, and young adults with Barth syndrome. J Inherit Metab Dis 42: 480–493.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Hornby B, McClellan R, Buckley L, Carson K, Gooding T, et al. (2019) Functional exercise capacity, strength, balance and motion reaction time in Barth syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis 14: 1–12.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Thompson WR, Decroes B, Mcclellan R, Rubens J, Vaz MF, et al. (2016) New targets for monitoring and therapy in Barth syndrome. Genet Med 18: 1001–1010.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Jacob ML, Johnco C, Dane BF, Collier A, Storch EA (2016) Psychosocial functioning in Barth syndrome: Assessment of individual and parental adjustment. Child Heal Care 46: 66–92.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Judd N, Calhoun H, Chu V, Reynolds S (2020) The Relationship Between Sleep and Physical Activity Level in Barth Syndrome: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. J Rare Dis Res Treat 5: 24–30.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Lim Y, Hayat M, Tripp N (2019) Impact on the Family of Raising Children With Rare Diseases: A Propensity Score Approach. Am J Occup Ther 73: p731151526.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Mazar I, Stokes J, Ollis S, Love E, Espensen A, et al. (2019) Understanding the life experience of Barth syndrome from the perspective of adults: A qualitative one-on-one interview study. Orphanet J Rare Dis 14: 1–8.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Babson I, Daw, E, Reynolds S (2022) Qualitative investigation of fatigue and its daily impacts as perceived by individuals with Barth Syndrome. J Rare Disord Diagn Ther 8: 1-9.

- Landfeldt E, Edstrom J, Buccella F, Kirschner J, Lochmüller H (2018) Duchenne muscular dystrophy and caregiver burden: A systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol 60: 987–996.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences