Vascular Complications of Neurofibromatosis Type 1-A Case Report and Literature Review with Special Emphasis on Pregnancy

Ruben Ploger*, Ulrich Gembruch, Waltraut M Merz, Sylvia LohfinkSchumm, Glen Kristiansen, Alexander Kania and Frauke Verrel

Published Date: 2022-06-29Ruben Ploger1*, Ulrich Gembruch1, Waltraut M Merz1, Sylvia Lohfink- Schumm2, Glen Kristiansen2, Alexander Kania3 and Frauke Verrel3

1Department of Obstetrics and Prenatal Medicine, University of Bonn Medical School, Bonn, Germany

2Department of Pathology, University of Bonn Medical School, Bonn, Germany

3Departments of General, Visceral, Thoracic and Vascular Surgery, University of Bonn Medical School, Bonn, Germany

- *Corresponding Author:

- Ruben

Ploger,

Department of Obstetrics and Prenatal Medicine,

University of Bonn Medical School, Bonn,

Germany,

Tel: 00491702860557

E-mail:ruben.ploeger@ukbonn.de

Received date: April 20, 2022, Manuscript No. IPRDDT-22-13256; Editor assigned date: April 25, 2022, PreQC No. IPRDDT-22-13256 (PQ); Reviewed date: May 10, 2022, QC No. IPRDDT-22-13256; Revised date: June 21, 2022, Manuscript No. IPRDDT-22-13256 (R); Published date: June 29, 2022, DOI: 10.36648/2380-7245.8.9.073

Citation: Ploger R, Gembruch U, Merz WM, Lohfink-Schumm S, Kristiansen G, et al. (2022) Vascular Complications of Neurofibromatosis Type 1–A Case Report and Literature Review with Special Emphasis on Pregnancy. J Rare Disord Diagn Ther Vol:8 No:9

Abstract

Vascular involvement in Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) may result in major hemorrhage due to the rupture of an affected vessel or during surgery for neurofibromas. Pregnancy in women with NF1 is characterized by disease specific and obstetric complications. These include an increase in number and size of neurofibromas, preeclampsia, placental abruption, fetal growth restriction, and preterm birth.

We present the case of a pregnant patient with NF1 who suffered a perioperative rupture of the left common iliac artery during her third cesarean section. To further investigate hemorrhagic complications in patients with NF1, and during pregnancy in particular, we performed a literature search. PubMed database was used covering the time between inception and October 2021. In all, 154 cases were included. With the exception of six these were single case reports. 143 non-obstetric cases were described (77 women (53%), 66 men (46%)). Median age was 45 years (IQR 36-53). Affected vessels were predominantly from the trunk (n=96, 67%), followed by head and neck (n=34, 24%) and limbs (n=13, 9%). Overall mortality was 21.6%, without difference between sex and location.

Reports of 11 pregnant or postpartum women were found. All antepartum incidents (n=4) occurred during the third trimester, and postpartum cases (n=7) within two weeks after delivery; three women (27.3%) died. Perinatal survival of cases with vessel ruptures during pregnancy was not reported (n=1), intrauterine fetal death (n=1), and survival (n=2) with poor and non-reported Apgar score, respectively.

Overall, 61 reports (39%) included histopathological findings. Elastin fragmentation, changes of the vessel wall structure, neurofibroma, or positive results for S-100 protein was commonly reported. Vessel ruptures in patients with NF1 are rare; the 21.6% mortality rate may be an underestimation. Female sex and the reproductive phase are overrepresented. The adverse association between pregnancy and NF1 may be attributable to the hormonal changes and the hyperdynamic cardiovascular state of pregnancy. Until now, screening and preventive measures of vascular complications in NF1 are not available. A high level of suspicion, immediate attention of a multidisciplinary team, with availability of large amounts of blood products are a prerequisite of successful treatment.

Abbreviations: IQR; Interquartile range; N number; NF1, Neurofibromatosis type 1

Keywords

Pregnancy complications; Pregnancy; Obstetrics; Neurofibromatosis type 1; Iliac artery; Ruptured aneurysm; Hemorrhage

Introduction

Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1, Mendelian Inheritance in Man #162200), is an autosomal dominant multisystem disease with an estimated prevalence of 1:3000 [1]. Located on 17q11.2, NF1 encodes neurofibromin, a tumor suppressor. The disease is characterized by a high phenotypic variability. Two or more of the following criteria need to be fulfilled: presence of more than six café-au-lait macules; two or more neurofibromas of any type or one plexiform neurofibroma; freckling in the axillary or inguinal regions; optic glioma; two or more Lisch nodules; a distinctive osseous lesion such as tibial pseudoarthrosis; or a first-degree relative diagnosed by the above citeria [2-4].

Vascular involvement of NF1 includes arterial dysplasia, stenosis, occlusion, ectasia and aneurysm formation. Major hemorrhage may occur as a result of rupture of the affected vessel, or during surgery for neurofibromas [5-6].

Pregnancy in affected women is characterized by NF1-specific and obstetric complications. These include, among others, an increase in number and size of neurofibromas, preeclampsia, placental abruption, fetal growth restriction, and preterm birth [7-10].

We present the case of a pregnant patient with NF1 who suffered an iliac artery rupture. For further investigation of hemorrhagic complications in patients with NF1, and during pregnancy in particular, we performed a literature search.

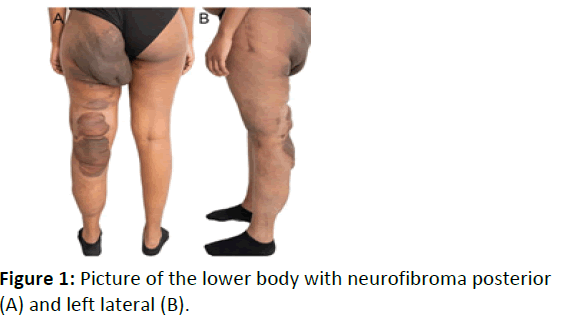

The patient’s diagnosis was established during childhood. There was no other affected family member. A genetic analysis had been performed during infancy, which had not revealed a pathogenic mutation. Her most prominent manifestation was the presence of multiple neurofibromas predominantly of the left lower body; corrective osteotomy of the left femoral head with excision of a neurofibroma had been performed during childhood (Figure 1A, B). Her obstetric history is summarized in Table 1.

| Pregnancy number/ maternal age | Complications during pregnancy | GA at delivery | Mode of delivery | Maternal complications postpartum | Fetal complication s | Newborn data | Neonatal complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18-Jan | Preterm labor, PROM, placental abruption | 36+6 | Emerge ncy CS | Lymphatic swelling in the left lower limb | Uteroplacent al dysfunction | F, 2390 g (15. P.), Apgar 2/6/7, UA-pH 6.67 |

Asphyxia, adrenal hemorrhage |

| 20-Feb | HELLP syndrome, placental abruption | 36+4 | CS | HELLP syndrome, AKI, ARDS, coagulopathy | Fresh stillbirth | M, 2900 g (41. P.) | n. a. |

| 24-Mar | Preterm labor | 35+2 | CS | Cardiovascular arrest immediately after CS; CPR, relaparotomy, ROSC after 32 min.; hemoperitoneum due to spontaneous rupture left common iliac artery; reconstruction with bovine patchplasty, retroperitoneal packing, embolization left ovarian artery | none | M, 2400 g (26. P.), Apgar 7/8/9, UA-pH 7.31 |

RDS, icterus |

AKI: Acute Kidney Injury; APGAR: Appearance, Pulse, Grimace, Activity, Respiration; ARDS: Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome; CPR: Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation; CS: Cesarean Section; F: Female; GA: Gestational Age; HELLP: Hemolysis, Elevated Liver Enzymes, Low Platelets; M: Male; NA: Not Applicable; P: Percentile; PROM: Premature Rupture of Membranes; RDS: Respiratory Distress Syndrome; ROSC: Return Of Spontaneous Circulation; UA: Umbilical Artery

Table 1: Obstetric details, case report.

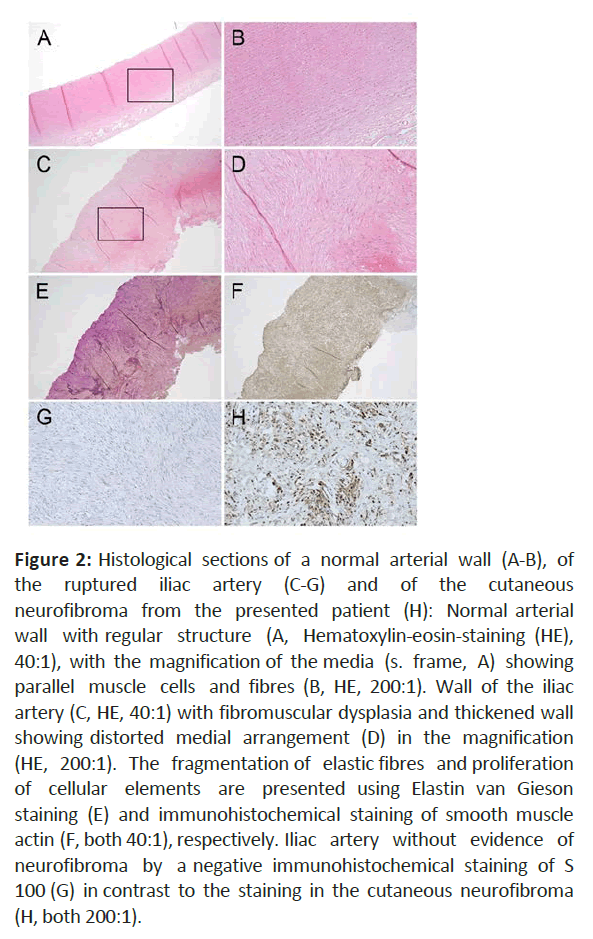

The histopathological examination of the iliac artery specimen revealed fibroid transformation of the vascular wall resulting in a disorganized structure of the smooth muscle cells (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Histological sections of a normal arterial wall (A-B), of the ruptured iliac artery (C-G) and of the cutaneous neurofibroma from the presented patient (H): Normal arterial wall with regular structure (A, Hematoxylin-eosin-staining (HE), 40:1), with the magnification of the media (s. frame, A) showing parallel muscle cells and fibres (B, HE, 200:1). Wall of the iliac artery (C, HE, 40:1) with fibromuscular dysplasia and thickened wall showing distorted medial arrangement (D) in the magnification (HE, 200:1). The fragmentation of elastic fibres and proliferation of cellular elements are presented using Elastin van Gieson staining (E) and immunohistochemical staining of smooth muscle actin (F, both 40:1), respectively. Iliac artery without evidence of neurofibroma by a negative immunohistochemical staining of S 100 (G) in contrast to the staining in the cutaneous neurofibroma (H, both 200:1).

Methods

For literature research, the PubMed database was used covering the time between inception and October 2021. The following terms were applied: neurofibromatosis and pregnancy, neurofibromatosis and aneurysm, and neurofibromatosis and ruptured vessel. The title and abstract of the retrieved publications were read to assess the relevance. Additionally, references of publications were hand-searched for further reports. Study design and language were not restricted.

Results

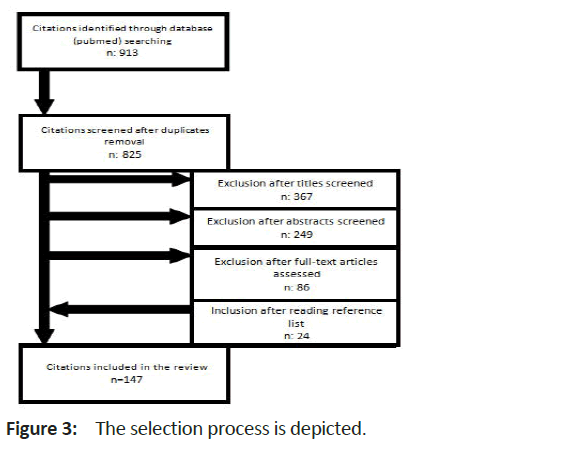

A total of 913 citations was retrieved. After exclusion of duplicates and screening of titles and abstracts, 233 full-text articles were assessed; additionally, references were hand searched for further citations. Finally, 147 publications were included. With the exception of six publications, which reported on two or three cases each, these were single-case reports (Figure 3) [11-16].

Non-obstetric cases were described in 137 reports (143 cases, in Table 1 supplementary), including 77 women (53%) and 66 men (46%), in supplementary Table 1. Median age was 45 (interquartile range (IQR) 36-53). Affected vessels were predominantly from the trunk (number (n)=96, 67%), followed by head and neck (n=34, 24%), and limbs (n=13, 9%). Treatment was successful in 108 of reported cases (76%) with survival of 77% for ruptures of trunk vessels, 73% for head and neck, and 69% for limb vessels. Outcome was not reported for four cases. Fatalities were equally distributed between women and men (15 and 16, respectively), corresponding to a 21.6% mortality rate.

Ten publications reported on 11 pregnant or postpartum women, see Table 2. Affected arteries were from the trunk (n=7), head and neck (n=3), and limb (n=1). All antepartum incidents (n=4) occurred during the third trimester, and postpartum cases within two weeks after delivery. Three women (27.3%) died. Perinatal survival of cases with vessel ruptures during pregnancy was not reported (n=1), intrauterine fetal death (n=1), and neonatal survival (n=2) with poor and non-reported Apgar score, respectively.

| Author | Age | GA / days pp | Affected artery | Treatment | Outcome | Period of hospital ization (days) | Country | Histopathology | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| maternal | fetal | ||||||||

| Tateishi et al. 2019 | 42 | 28 | Ascending aorta | CS; hysterectomy; ascending aorta replacement | survived | survived 1482 g | 67 | JP | Break in medial elastic fibers. Positive cells for S-100 protein in the media, no neurofibroma |

| Hashimoto et al. 2021 | 39 | 34 | L. intercostal causing hematothorax | CS; endovascular embolization | survived | n. r. | 30 | JP | n. r. |

| Tidwell and Copas 1998 | 30 | 34 | R. brachial | Initially venous replacement; transhumeral amputation after recurrence | survived | urvived 2721 g APGAR 2/3/-s |

30 | US | Invasion of neurofibroma into the vessel wall |

| Tapp and Hickling 1969 | 35 | 35 | R. renal | Resuscitation | died unoperated | IUFT, IUFT, apparently normally developed fetus, 2400g | - | UK | Neurofibromatous thickening |

| Brady and Bolan 1984 | 35 | 2 | R. subclavian | - | died survived | alive | -25 | US US | Neurofibroma Fibrovascular tissue |

| 26 | 5 | L. intercostal | Suture ligations | alive | |||||

| Serleth et al. 1998 | 20 | 3 | Pancreaticoduodena l aneurysms | Embolization for unruptured aneurysms; laparotomy with ligation for ruptured aneurysms | survived | alive 1900g | 54 | US | n. r. |

| Narasimma n et al. 2019 | 33 | 4 | R. intrathoracic intercostal AVMs | R. thoracotomy; ligation and excision | survived | alive | 30 | MY | mesenchymal proliferative lesions, cells positive for S-100 protein, neurofibroma plexiforme without atypia. |

| Sánchez- Contreras et al. 2020 | 36 | 7 | L. common iliac | Laparotomies for recurrent ruptures; L. aorto-iliac bypass | died | n. r. | n. r. | ES | Thinning of the aortic wall |

| Smith et al. 2000 | 28 | 10 | L. internal carotid | Endoluminal stent graft; ligation | survived | alive (twins) | 18 | US | Neurofibroma |

| Roth et al. 2000 | 36 | 14 | L. vertebral | Endovascular embolization | survived | alive | 2 | US | n. r. |

APGAR: Appearance, Pulse, Grimace, Activity, Respiration; AVM: Arteriovenous Malformation; CS: Cesarean Section; ES: Spain; GA: Gestational Age; IUFT: Intrauterine Fetal Death; JP: Japan; L: Left; pp: Days Post-Partum; MY: Malaysia; NR: Not Reported; R: Right; UK: United Kingdom; US: United State of America.

Table 2: Publications of vessel ruptures during pregnancy and postpartum in women with Neurofibromatosis Type 1.

Overall, 61 reports (39%) included a description of the histopathological findings. Elastin fragmentation and changes of the vessel wall structures were common features; likewise, neurofibroma or positive results for S-100 protein, a Schwann cell marker, was reported. In our case the wall of the ruptured iliac artery exhibits a thickened media with disrupted elastic fibers and increased smooth muscle cells in a disorderly arrangement. The intima of the iliac artery is not reliably depictable, the adventitia shows a discrete fibrosis. There is no evidence of interposed neurofibroma [17-19].

Discussion

Vessel ruptures in patients with NF1 are rare, illustrated by the fact that only case reports have been published. The mortality rate of 21.6% may be an underestimation. Most severe cases may go undiagnosed since they do not reach hospital in time for treatment. This assumption is supported by our own case, who went into hemorrhagic shock with cardiorespiratory arrest within two minutes after onset of symptoms; survival, and even survival without neurologic sequelae after 32 minutes to the return of spontaneous circulation was owed to the fact that the rupture occurred within the theatre premises of a large level I referral center, with immediate availability of specialists in vascular surgery and anesthesia, and blood products [20-23].

With 7.1% of reported cases covering pregnancy and the postpartum period, and the majority of published cases in the non- pregnant population reporting on women, female sex and the reproductive phase in particular, are overrepresented.

An adverse association between pregnancy and NF1 has been previously reported. The increase in number of café-au-lait spots and accelerated growth of neurofibromas has been attributed to the hormonal changes of pregnancy, especially to the rise in steroid hormone concentrations [24]. The hyperdynamic cardiovascular state of pregnancy, consisting of an increase in blood volume and cardiac output of some 40% may additionally contribute to the rupture of an affected vessel wall. No difference was present in the location of vessel rupture between pregnant and non- pregnant cases.

Results of our investigation are characterized by several limitations. These comprise the type of included publications. The risk of bias is particularly high for case reports. However, these were the only publications available. Furthermore, survival rates may be overestimated since non-successful cases may not be reported; additionally, cases may go undiagnosed if they do not reach hospital in time and postmortem diagnosis is not performed. Publication bias may also explain the high number of reports during pregnancy and postpartum. However, since women with NF1 tend to have a lower than average pregnancy rate, the risk of arterial rupture during pregnancy may even be higher.

Conclusion

In conclusion, vessel rupture is a rare but devastating complication of patients with NF1. Until now, screening and preventive measures are not available. A high level of suspicion, an immediate attention of a multidisciplinary team of (vascular) surgeons, anesthetists, radiologists, and in case of pregnancy. Obstetricians, with availability of large amounts of blood products are a prerequisite of successful treatment.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

No Funding.

Authors contributions

RP: literature review; Data analysis; Manuscript writing. SLS and GK: histological examination; Manuscript writing. AK and FV: surgical management; UG: prenatal management, manuscript writing. WMM: Data analysis; Patient management coordination; Manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

References

- Lammert M, Friedman JM, Kluwe L, Mautner VF (2005) Prevalence of Neurofibromatosis 1 in German Children at Elementary School Enrollment. Arch Dermatol 141: 71-74

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Friedman JM, Jett K (2010) Clinical and genetic aspects of neurofibromatosis 1. Genet Med 12:1–11

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Antonio JR, Goloni-Bertollo EM, Tridico LA (2013) Neurofibromatosis: chronological history and current issues. An Bras Dermatol 88:329–343

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Wilson BN, John AM, Handler MZ, Schwartz RA (2021) Neurofibromatosis type 1: New developments in genetics and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol 84:1667–1676

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Friedman JM (2019) Neurofibromatosis 1. Eur J Hum Genet 15:131–138

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Bergqvist C, Servy A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Ferkal S, Combemale P, et al. (2020) Neurofibromatosis 1 French national guidelines based on an extensive literature review since 1966. Orphanet J Rare Dis 15:1-24

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Roth TM, Petty EM, Barald KF (2008) The role of steroid hormones in the NF1 phenotype: Focus on pregnancy. Am J Med Genet 146:1624–1633

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Chetty SP, Shaffer BL, Norton ME (2011) Management of Pregnancy in Women with Genetic Disorders: Part 2: Inborn Errors of Metabolism, Cystic Fibrosis, Neurofibromatosis Type 1, and Turner Syndrome in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv 66:765–776

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Terry AR, Barker FG, Leffert L (2013) Neurofibromatosis type 1 and pregnancy complications: a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 209:461-468

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Leppavirta J, Kallionpaa RA, Uusitalo E, Vahlberg T, Poyhonen M, et al (2017) The pregnancy in neurofibromatosis 1: A retrospective register-based total population study. Am J Med Genet 173:2641–2648

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Brady DB, Bolan JC (1984) Neurofibromatosis and spontaneous hemothorax in pregnancy: two case reports. Obstet Gynecol 63:35-38

[Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Slisatkorn W, Subtaweesin T, Laksanabunsong P, Warnnissorn M (2003) Spontaneous Rupture of the Left Subclavian Artery in Neurofibromatosis. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 11:266–268

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Miura T, Kawano Y, Chujo M, Miyawaki M, Mori H, et al. (2005) Spontaneous hemothorax in patients with von Recklinghausen’s disease. Jpn J Thorac Caridovasc Surg 53:649–652

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Arai K, Sanada J, Kurozumi A, Watanabe T, Matsui O (2007) Spontaneous Hemothorax in Neurofibromatosis Treatedwith Percutaneous Embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 30:477–479

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Kanematsu M, Kato H, Kondo H, Goshima S, Tsuge Y, et al. (2011) Neurofibromatosis Type 1: Transcatheter Arterial Embolization for Ruptured Occipital Arterial Aneurysms. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 34:131–135

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Attia M, Gharsalli H, Rmili H, Affes M, Ben Saad S, et al. (2019) Spontaneous hemothorax and neurofibromatosis type 1: How to explain it, how to explore it and how to treat it? Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 89:213-216

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Tateishi A, Okada M, Nakai M, Yokota Y, Miyamoto Y, et al. (2019) Spontaneous ascending aortic rupture in a pregnant woman with neurofibromatosis type 1. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 67:979–981

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Hashimoto K, Nomata Y, Fukui T, Takada A, Narita K, et al. (2021) Massive hemothorax in a pregnant patient with neurofibromatosis type 1. J Cardiothorac Surg 16:1-4

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Tidwell C, Copas P (1998) Brachial artery rupture complicating a pregnancy with neurofibromatosis: A case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol 179:832–834

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Tapp E, Hickling RS (1969) Renal artery rupture in a pregnant woman with neurofibromatosis. J Pathol 97:398–402

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Serleth HJ, Cogbill TH, Gundersen SB (1998) Ruptured pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysms and pheochromocytoma in a pregnant patient with neurofibromatosis. Surgery 124:100–102

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Narasimman S, Govindasamy H, Seevalingam KK, Paramasvaran G, Ramasamy U (2019) Spontaneous massive haemothorax in the peri-partum period of an undiagnosed neurofibromatosis type 1 patient - A surgical perspective. Med J Malaysia 74:99–101

[Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Smith BL, Munschauer CE, Diamond N, Rivera F (2000) Ruptured internal carotid aneurysm resulting from neurofibromatosis: treatment with intraluminal stent graft. J Vasc Surg 32:824– 828

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Sanchez-Contreras MD, Sanchez-Andres C, Valiente Mateos M, Ayas Faus G, Domingo Triadó V (2020) Massive spontaneous haemoperitoneum in a post-partum patient with neurofibromatosis type 1. Anesth Resusc 67:219–222

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences