Splenic, Hepatic and Gastric Sarcoidosis: Case Study

Nawal Lagdali*, Camelia Berhili, Maryeme Kadiri, Fatima Zahra Habib, Imane Benelbarhdadi, Mohamed Borahma and Fatima Zahra Ajana

Department of Hepato-Gastroenterology C, Mohamed V University, Rabat, Morocco

DOI10.36648/2380-7245.10.1.145

Nawal Lagdali*, Camelia Berhili, Maryeme Kadiri, Fatima Zahra Habib, Imane Benelbarhdadi, Mohamed Borahma and Fatima Zahra Ajana

Department of Hepato-Gastroenterology C, Mohamed V University, Rabat, Morocco

- *Corresponding Author:

- Nawal Lagdali

Department of Hepato-Gastroenterology C,

Mohamed V University, Rabat,

Morocco,

E-mail: nawal.lagdali@gmail.com

Received date: January 05, 2024, Manuscript No. IPRDDT-24-18538; Editor assigned date: January 08, 2024, PreQC No. IPRDDT-24-18538 (PQ); Reviewed date: January 22, 2024, QC No. IPRDDT-24-18538; Revised date: January 31, 2024, Manuscript No. IPRDDT-24-18538 (R); Published date: February 22, 2024, DOI: 10.36648/2380-7245.10.1.145

Citation: Lagdali N, Berhili C, Kadiri M, Habib FZ, Benelbarhdadi I, et al. (2024) Splenic, Hepatic and Gastric Sarcoidosis: Case Study. J Rare Disord Diagn Ther Vol.10 No.1:145.

Abstract

Introduction: Sarcoidosis is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by the formation of granulomas, or small clusters of inflammatory cells, in various organs throughout the body.

Case: Biological assessment shows anicteric cholestasis with elevated levels of GGT and ALP. Despite negative results for hepatitis B and C, a diagnosis of sarcoidosis is suspected due to the presence of granulomatous hepatitis and portal fibrosis.

Discussion: Gastric sarcoidosis is a rare form of sarcoidosis that affects the stomach. It is estimated to occur in less than 1% of sarcoidosis cases.

Conclusion: In addressing the complex nature of multiorgan sarcoidosis, the case study underscores the necessity of ongoing research to enhance diagnostic tools and refine treatment strategies.

Keywords

Sarcoidosis; Multiorgan; Granulome; Biopsy; Histopathology

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by the formation of granulomas, or small clusters of inflammatory cells, in various organs throughout the body. While the disease can affect any organ, involvement of the liver and spleen (hepatic and splenic sarcoidosis, respectively) is relatively rare.

Case Report

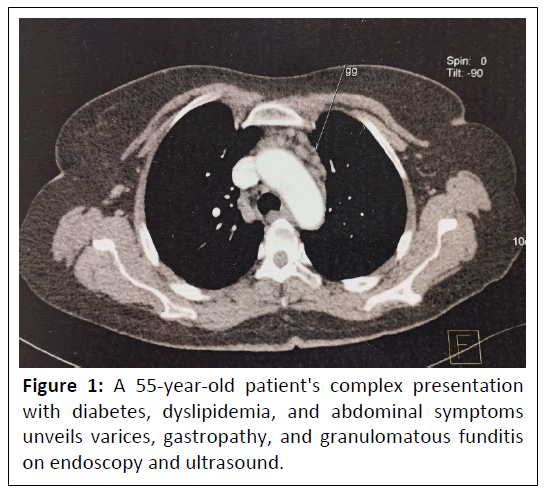

This case study describes a 55-year-old patient with a history of type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia who presents with atypical abdominal pain and upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The patient's symptoms have been ongoing for a year. Clinical examination reveals splenomegaly, and an endoscopy shows grade III varices and hypertensive gastropathy. Biopsies taken during the endoscopy reveal non-necrotizing granulomatous funditis. An abdominal ultrasound shows a heterogeneous liver, with a slightly thickened wall and perivesicular ascites, as well as a globular nodular spleen measuring 14.5 cm, and permeable and dilated portal vein shows in Figure 1.

Biological assessment shows anicteric cholestasis with elevated levels of GGT and ALP. Despite negative results for hepatitis B and C, a diagnosis of sarcoidosis is suspected due to the presence of granulomatous hepatitis and portal fibrosis. To rule out tuberculosis, a quantiferon test and thoracic scan are performed, which show pulmonary micronodules and multiple subcentimetric lymph nodes in the para-aortic region, but no definitive diagnosis can be made.

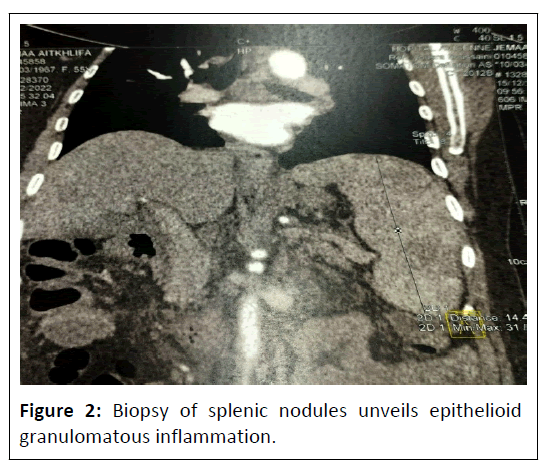

Given the inability to conclude a certain diagnosis and the non-feasibility of biopsy of the thoracic lymph nodes, a biopsy of the splenic nodules is performed, which reveals epithelioid granulomatous inflammation without caseous necrosis. Based on this information, the diagnosis of hepatic, splenic, and gastric sarcoidosis is retained and the patient is started on corticosteroid therapy at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg (Figure 2).

In expanding upon the comprehensive management of multiorgan sarcoidosis, the treatment course outlined in the case study provides insight into the challenges of achieving optimal therapeutic outcomes. The initiation of corticosteroid therapy at 0.5 mg/kg demonstrated initial efficacy, corroborating the standard approach for managing sarcoidosis. However, the subsequent development of ascites prompted the introduction of aldactone and necessitated a reduction in corticosteroid therapy, highlighting the dynamic nature of sarcoidosis and the need for adaptive treatment strategies.

The installation of ascites, underscores the unpredictable nature of sarcoidosis and the potential for varied responses to corticosteroid therapy. While corticosteroids remain a mainstay in the treatment arsenal, their side effects and the variability in patient response necessitate a careful balance in dosage and duration. The introduction of aldactone reflects the nuanced approach required in managing complications on portal hyopertension, emphasizing the importance of continuous monitoring and adjustment of the treatment plan.

Results & Discussion

Hepatic sarcoidosis is estimated to occur in less than 5% of sarcoidosis cases, and can present with a wide range of symptoms, from asymptomatic to severe liver dysfunction. The diagnosis of hepatic sarcoidosis is often challenging and may require a combination of imaging techniques, such as Computed Tomography (CT) or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), and biopsy of the liver tissue. Treatment options for hepatic sarcoidosis include corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive drugs, but in some cases, the disease may resolve on its own without treatment [1,2].

Splenic sarcoidosis is even rarer, with an estimated incidence of less than 1%. The spleen is often involved in sarcoidosis along with other organs, and the symptoms are often non-specific and include abdominal pain, an enlarged spleen, and fatigue. The diagnosis of splenic sarcoidosis is also often challenging, and may require imaging studies such as CT or MRI and biopsy of the spleen. Treatment options for splenic sarcoidosis include corticosteroids, immunosuppressive drugs, and in some cases, surgical removal of the spleen [1,3].

Gastric sarcoidosis is a rare form of sarcoidosis that affects the stomach. It is estimated to occur in less than 1% of sarcoidosis cases. The symptoms of gastric sarcoidosis are often non-specific and can include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and weight loss. Gastric sarcoidosis can also cause complications such as bleeding and perforation.

The diagnosis of gastric sarcoidosis is often challenging and may require a combination of imaging studies, such as endoscopy and Computed Tomography (CT), and biopsy of the stomach tissue. Endoscopy can reveal characteristic findings such as granulomas, ulceration, and nodularity of the stomach mucosa. However, these findings are not specific to sarcoidosis and can be seen in other inflammatory and neoplastic conditions. Biopsy is necessary to confirm the diagnosis of sarcoidosis [1-5].

Treatment options for gastric sarcoidosis include corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive drugs, but the disease may resolve on its own without treatment. In cases where the disease is causing severe symptoms or complications, surgery may be necessary to remove affected portions of the stomach [6,7].

Conclusion

In addressing the complex nature of multi-organ sarcoidosis, the case study underscores the necessity of ongoing research to enhance diagnostic tools and refine treatment strategies. The use of a combination of imaging studies, biopsies, and laboratory tests is essential in making an accurate diagnosis and determining the appropriate course of treatment. It also shows the importance of ruling out other potential causes of granulomatous inflammation such as tuberculosis.

Collaborative efforts between clinicians, radiologists, pathologists, and other specialists become paramount in navigating the intricate landscape of sarcoidosis management. This holistic approach ensures that patients receive the most tailored and effective interventions, considering both the diversity of organ involvement and the dynamic nature of the disease course. Overall, the case study serves as a valuable illustration of the intricate decision-making process in managing multi-organ sarcoidosis and prompts further exploration of personalized therapeutic approaches in the realm of this challenging inflammatory disorder.

References

- Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS (2007) Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med 357: 2153-2165.

- Vardhanabhuti V, Venkatesh SK (2010) Imaging of hepatic sarcoidosis: A review. AJR Am J Roentgenol 195: 33-39.

- Ungprasert P, Carmona EM, Crowson CS, Matteson EL (2017) Diagnostic utility of splenic biopsy in sarcoidosis: A population-based study. Eur J Clin Invest 47: 251-256.

- Gupta N, Vakde T, Gupta S (2015) Sarcoidosis of the stomach: A case report and review of the literature. Gastroenterol Rep. 3: 84-87.

- Nunes H, Bouvry D, Soler P, Valeyre D (2008) Sarcoidosis-associated gastrointestinal involvement: Diagnosis and management. Am J Gastroenterol 103: 2367-2373.

- Baughman RP, Lower EE, du Bois RM (2003) Sarcoidosis. Lancet 362: 1113-1125.

- Nunes H, Bouvry D, Soler P, Valeyre D (2007) Sarcoidosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2: 46.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences