A Stroke Chameleon Presenting as Alien Hand Syndrome

Tamara Al Bahri*

Department of Neurology, Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield, United Kingdom

- *Corresponding Author:

- Tamara Al Bahri

Department of Neurology,

Royal Hallamshire Hospital,

Sheffield,

United Kingdom;

Email: tamara.albahri@gmail.com

Received: May 22, 2020 Manuscript No. IPRDDT-23-4228; Editor assigned: May 27, 2020, PreQC No. IPRDDT-23-4228 (PQ); Reviewed: June 10, 2020, QC No. IPRDDT-23-4228; Revised: November 8, 2023, Manuscript No. IPRDDT-23-4228 (R); Published: December 6, 2023, DOI: 10.36648/2380-7245.9.5.131

Citation: Bahri TA (2023) A Stroke Chameleon Presenting as Alien Hand Syndrome. J Rare Disord Diagn Ther Vol.9 No.5:131.

Abstract

Stroke chameleons are uncommon presentations of stroke that resemble other clinical diagnoses. A 70-year-old righthanded man presented to the movement disorders clinic reporting that his left arm was jumping all over the place. The involuntary movements gradually settled over the following weeks and he was left with a numb sensation on the left side of the neck, left arm and trunk.

Keywords

Stroke; Numb sensation; Movement disorders; Chameleons

Introduction

Stroke chameleons are uncommon presentations of stroke that resemble other clinical diagnoses. These chameleons can present as neuropsychiatric symptoms, acute confusional state, altered level of consciousness, seizures and movement disorders. The latter includes Alien Hand Syndrome (AHS), which usually affects the left arm. First described by Goldstein in 1908 as a motor apraxia, the term ‘alien hand’ comes from the French ‘main etrangere’ which Brion, et al. used to describe the foreignness of the limb in patients with corpus callosum lesions. AHS is defined by two criteria: The hand moves involuntarily and acts as though it has its own will. The alien hand moves without the individual’s intention and control and can be viewed as wayward or disobedient, performing movements such as touching the face and removing bed covers. Here, we describe this unusual presentation of acute ischaemic stroke [1].

Case Presentation

A 70-year-old right-handed man presented to the movement disorders clinic reporting that his left arm was jumping all over the place. His symptoms started a month earlier when his arm movements woke him up from sleep, touching him and moving spontaneously outside his control. His arm would shoot upwards, needing to be controlled by his right hand. It would grab things in his surroundings without his conscious will and he felt it did not belong to him. This caused difficulties with tasks requiring both hands, such as buttoning his shirt. The involuntary movements gradually settled over the following weeks and he was left with a numb sensation on the left side of the neck, left arm and trunk. His left arm was not weak, but he was unable to maintain its posture and struggled to hold a cup. The other limbs, face, vision and speech were not affected. He had hypertension and hyperlipidaemia and was on aspirin, atorvastatin, lansoprazole and naproxen [2].

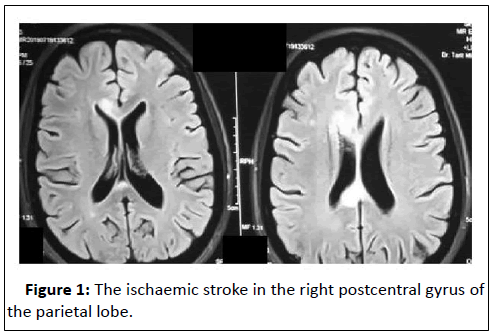

On examination, he had a mild left facial droop. Cranial nerves were intact and power and sensation to pinprick, fine touch and vibration were normal in all limbs. However, he had astereognosis and agraphesthesia in the left hand, suggesting cortical sensory loss. He had mild left dysdiadochokinesia and bilateral intention tremor, but no bradykinetic rigidity. Reflexes were brisk in the left arm and plantar responses were flexor bilaterally. There was no ataxia [3]. Differential diagnoses included stroke and a degenerative syndrome such as corticobasal degeneration. Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) showed an established ischaemic stroke in the right postcentral gyrus of the parietal lobe (Figure 1) [4].

A 72-hour Holter monitor showed no paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. A carotid ultrasound showed lumen diameter loss of less than 50% bilaterally. Aspirin was changed to clopidogrel and he was advised to continue the same dose of atorvastatin [5].

Results and Discussion

Most strokes normally present with focal neurological deficits. However, a retrospective study found that stroke chameleons make up 22% of ischaemic strokes. With stroke incidence in the UK being more than 100,000 a year, this means that at least 22,000 could initially be missed, reducing the opportunity for early intervention. Although rare, recognising AHS as a stroke chameleon is vital [6].

AHS can also result from tumours, trauma, infection or degenerative disease. In a literature review by Scepkowski, et al, frontal, callosal and posterior subtypes were used to describe AHS. The frontal type afflicts the dominant hand, resulting from left medial frontal and callosal damage. Patients develop a grasp reflex and compulsive tool manipulation. Damage to the corpus callosum with or without bilateral or right frontal lesions causes the callosal type, affecting the nondominant hand. In this type, patients develop intermanual conflict, where one hand acts at cross-purposes with the other. Posterior AHS is less commonly described and is caused by injury to the thalamus and parietal, occipital and temporal lobes. It causes uncoordinated purposeless hand movements, arm levitation and feeling of foreignness [7]. By these definitions, our patient had posterior AHS as he exhibited all these signs. However, he also had semipurposeful movements such as grasping objects in his surroundings, similar to the frontal type. This is also seen in other cases of posterior AHS [8].

A study using functional MRI showed that in a patient with AHS caused by parietal stroke, there was isolated activation of the contralateral primary motor cortex, as opposed to the orchestrated activation of neural networks when a voluntary movement is made. The premotor cortex generates an internal copy of a movement which is relayed to the somatosensory cortex of the parietal lobe. The somatosensory feedback generated by a movement is compared to this internal copy. If they correlate, the movement is interpreted as self-generated rather than due to an external force. In AHS, there is a deficit in creating this internal model, causing the individual to mistakenly interpret a self-generated movement as one produced by an external force. This could explain the loss of sense of agency [9].

Our patient was able to grasp an object in his left hand; however, he would drop it soon after, indicating a failure to maintain the action, possibly due to the inability to consciously monitor his motor intention. A study by Sirigu, et al., showed that the parietal lobe plays a critical role in this function and suggests that parietal lobe stroke can cause AHS by disrupting cortico-cortical sensorimotor processing loops responsible for the awareness of the motor movement [10].

Conclusion

We describe an unusual presentation of stroke in an elderly hypertensive male who had a sudden onset of AHS due to a posterior parietal stroke.

Parietal lobe lesions can cause AHS by interfering with the awareness of planned movements. AHS is a rare disorder that can be mistakenly diagnosed as a psychiatric illness or myoclonus. Therefore, any movement disorder that presents acutely should be investigated for stroke. A thorough neurological examination may reveal additional deficits such as sensory changes, visual field defects and brisk reflexes. We recommend a low threshold to be adopted for arranging brain imaging.

Patient Consent

The patient has kindly consented to the publishing of this case.

References

- Huff JS (2002) Stroke mimics and chameleons. Emerg Med Clin 20: 583-595.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brion S (1972) Disorders of interhemispheric transfer (callosal disonnection). 3 cases of tumor of the corpus callosum. The strange hand sign. Rev Neurol 126: 257-266.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gheewala G, Gadhia R, Surani SR, Ratnani I, Surani S (2019) Posterior alien hand syndrome from acute ischemic left parietal lobe infarction. Cureus 11: e5828.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arch AE, Weisman DC, Coca S, Nystrom KV, Wira III CR, et al. (2016) Missed ischemic stroke diagnosis in the emergency department by emergency medicine and neurology services. Stroke 47: 668-673.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scepkowski LA, Cronin-Golomb A (2003) The alien hand: Cases, categorizations and anatomical correlates. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev 2: 261-277.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Assal F, Schwartz S, Vuilleumier P (2007) Moving with or without will: Functional neural correlates of alien hand syndrome. Ann Neurol 62: 301-306.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nowak DA, Engel A, Leutbecher M, Zeller C (2020) Alien limb phenomenon following posterior cerebral artery stroke: A distinct clinical entity. J Neurol 267: 95-99.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sirigu A, Daprati E, Ciancia S, Giraux P, Nighoghossian N, et al. (2004) Altered awareness of voluntary action after damage to the parietal cortex. Nat Neurosci 7: 80-84.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wallace EJ, Liberman AL (2021) Diagnostic challenges in outpatient stroke: Stroke chameleons and atypical stroke syndromes. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 17: 1469-1480.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sarkar P, Ray BK, Mukherjee D, Pandit A, Ghosh R, et al. (2022) Alien limb phenomenon after diffuse corpus callosum ischemic stroke. Neurohospitalist 12: 295-300.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences