A Right Hypochondrial Discharging Sinus not to be Missed-"Spontaneous Cholecystocutaneous Fistula"

A R M Isthiyak* and Anura SK Banagala

Department of General Surgery, National Hospital of Sri Lanka, Colombo, Sri Lanka

- *Corresponding Author:

- A R M Isthiyak

Department of General Surgery,

National Hospital of Sri Lanka, Colombo,

Sri Lanka,

E-mail: dristhiyak@gmail.com

Received date: February 27, 2023, Manuscript No. IPRDDT-23-15970; Editor assigned date: March 01, 2023, PreQC No. IPRDDT-23-15970 (PQ); Reviewed date: March 10, 2023, QC No. IPRDDT-23-15970; Revised date: March 20, 2023, Manuscript No. IPRDDT-23-15970 (R); Published date: March 27, 2023, DOI: 10.36648/iprddt.9.3.94

Citation: Isthiyak ARM, Banagala ASK (2023) A Right Hypochondrial Discharging Sinus not to be Missed-"Spontaneous Cholecystocutaneous Fistula". J Rare Disord Diagn Ther Vol. 9 No.3:94

Abstract

Spontaneous Chole-Cystocutaneous Fistula (CCF) is a rare complication of cholelithiasis, which has only been reported a few times in the literature. We report the case of a 59 years old woman who presented with a discharging sinus in the epigastrium. CCF is a type of external biliary fistula, which connects the gallbladder with the skin. Thilesus first described this phenomenon in 1670. There is usually a history of calculi in the gallbladder or neglected gallbladder disease. The incidence of CCF is rare, most patients being elderly females with the mean age of 72.8 years old. Ultrasound, CT, MRI, MRCP and (CT or X-ray) fistulogram are used to confirm the diagnosis. CT was more significant than US in identifying the fistulous tract. Open cholecystectomy with excision of the fistulous tract is considered an acceptable option for treatment and it is curative in most cases. However, laparoscopic approach can be another option in experienced hands. Our patient underwent hepaticojejunostomy with en block skin, aponeurotic muscle, fistula tract, gallbladder, cystic duct, part of the common bile duct and hepatic duct excision. This case report demonstrates that maintaining a high degree of suspicion of this rare entity is helpful in achieving correct preoperative diagnosis and that computed tomography scan should be performed in all cases of unexplained abdominal wall suppuration or cellulitis.

Keywords

Cholecystitis; Cholesctyocutaneous fistula; Hepaticojejunostomy; Fistulogram; Gallstones; Laparotomy; Bile ducts

Introduction

Fistula is a pathological condition, which results from abnormal connection between two epithelialized surfaces. Gallstone diseases predispose to biliary fistulas in rare occasions that connect between the biliary tract and other organs. Biliary fistulas are classified as: Internal and external [1]. Internal biliary fistula connects the gallbladder with gastrointestinal tract; it results from chronic cholecystitis [2]. External biliary fistula connects the gallbladder with abdominal wall, it can be spontaneous, postoperative or post-traumatic or caused by iatrogenic injury of biliary tract [1,3].

Chole-Cystocutaneous Fistula (CCF) is a type of external biliary fistula, which connects the gallbladder with skin. In the medical history, there are less than 100 cases of cholecystocutaneous fistula reported. The first person who described and reported this pathological condition is Thilesus in 1670. However, during that era, fistulas were a common complication of chronic and untreated cholecystitis.

In total 226 cases have been reported, with fewer than 25 in the last 50 years, in the year 2005 studies [4]. Nowadays, the most rapid diagnosis and treatment with antibiotics or surgery significantly brought down the number of CCF cases. Apart from gallstone disease, CCF is reported in acalculous cholecystitis and carcinoma of the gallbladder.

The most common location for the exit tract of the fistula is the right upper quadrant, but locations such as the gluteal region, umbilicus and right groin have also been reported [4]. CCF is mostly seen in women over 60 years of age but there are reported cases in younger patients of 24 years. Therefore, we report a case of a cholecystocutaneous fistula in a patient with previously undiagnosed gallstone disease.

Case Summary

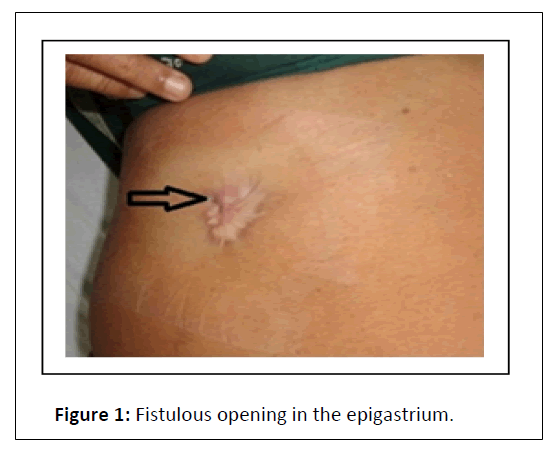

A 59-year-old woman with the history of hypertension and dyslipidemia was directed to our hospital from a private sector with complaints of pain in the abdomen and discharging sinus in the epigastrium for two years. She has had done an excision biopsy of epigastric sinus one year back at a different hospital and histology revealed active chronic inflammation (Figure 1).

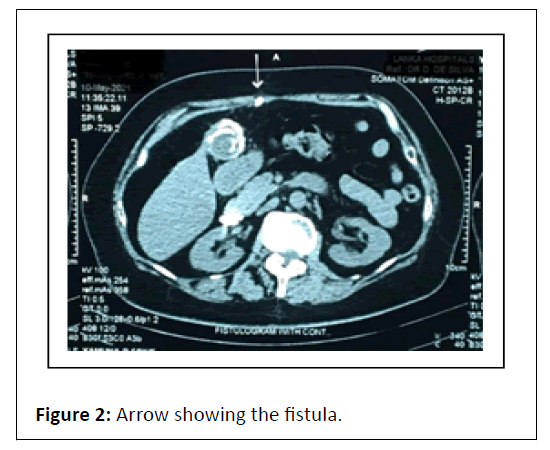

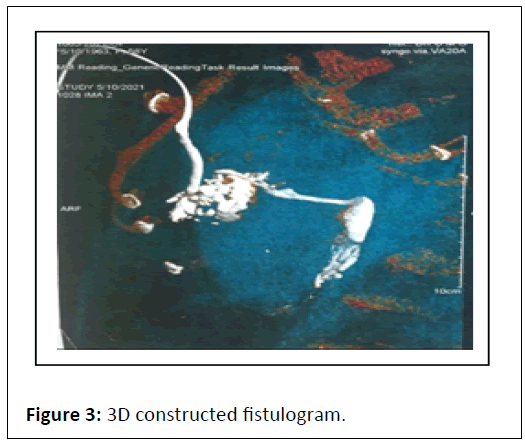

Ultrasound of the abdomen showed 2 cm tract in anterior abdominal wall in the epigastrium appears to communicate with peritoneal cavity, in favor of fistula formation with background chronic cholecystitis and gallbladder calculi (Figure 2). Subsequently CT fistulogram was performed and findings were diagnostic of cholecystocutaneous fistula (Figure 3).

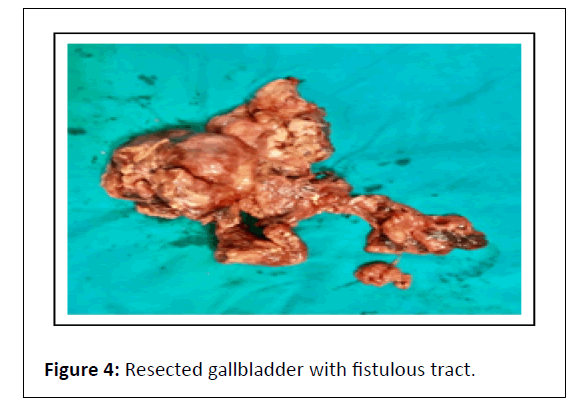

Liver function tests were normal and there were no contraindications for surgery under general anesthesia. We performed laparoscopy and decided to convert to open surgery due to difficulty in demonstrating the anatomy at the Calot’s triangle. At laparotomy, the fistulous tract was demonstrated and found to enter the fundus of the gallbladder (Figure 4). Gallbladder was thick, fibrotic and hard in consistency and was seen to adhere to the liver, with surrounding hard induration of the liver and also the cystic duct-common hepatic duct junctional area, raising the suspicion of carcinoma of the gallbladder. There were several large and hard stones within the gallbladder. We preceded with en bloc excision of aponeurotic muscle, skin and fistulous tract together with the gallbladder and a 5 cm cuff of the liver and cystic duct-common hepatic duct junction and the common bile duct down to the level of the superior border of the duodenum. A jejunal Roux-en-Y loop was raised and end to side hepaticojejunostomy performed with 5/0 polydioxanone interrupted sutures. The drain was kept in subhepatic region and patient received broad-spectrum antibiotics during and after surgery. The patient expressed a slow but uncomplicated recovery and was discharged home well on post-op D6. Superficial wound infection was noted on D9, which was managed with oral antibiotics and by D20 wound was completely healed. Histology of the specimen revealed acute on chronic cholecystitis, with a fistula between the skin and the lumen of the gall bladder, with no evidence of malignancy or tuberculosis.

Results and Discussion

The better understanding of pathology and evolution of sophisticated investigations lead to a rare occurrence of spontaneous cholecystocutaneous fistula. Less than 20 cases of spontaneous CCFs have been reported over the past 50 years [4]. A neglected biliary tract disease is being the culprit of cholecystocutaneous fistula. They are usually painless and commonly appear in the right upper quadrant. Moreover, they have been demonstrated at the umbilicus, left costal margin, right iliac fossa, right groin and the back [5]. The external opening of the fistula can mimic a pyogenic granuloma, infected epidermal inclusion cyst, chronic osteomyelitis of ribs, enterocutaneous fistula, discharging tuberculosis or metastatic carcinoma. The nature of the discharge from the fistula can be purulent, mucoid or bile depending on the patency of the cystic duct.

In a modern literature, Kaminsky reported on the frequency of biliary fistula to the gastrointestinal tract. The majority of the fistulas occur with connection to the duodenum (60%), followed by the colon (24%), stomach (6%) and choledochal duct (5%). Out of all, only 2% cholecystocutaneous abscesses or fistulas are accounted. Major risk factors for the development of spontaneous CCFs are: Elderly females (>50 years), steroid therapy, history of typhoid, bacterial dissemination, trauma, immunocompromised conditions, etc.

The pathophysiology of CCF can be studied step by step in following manners: Cholecystocutaneous fistula is a sequalae of increased pressure in the gallbladder, secondary to cystic duct obstruction, either caused by a calculus or neoplasia. The intraluminal pressure slowly builds up and leads to impairment of the blood flow and lymph supply to the gallbladder, thus causing mural necrosis and perforation. Perforation can be described as follows: 1) acute-free perforation leading to peritonitis 2) subacute perforation resulting in an abscess around the gallbladder 3) chronic perforation with the formation of an internal or external biliary fistula. These fistulas, as presented in this case, most frequently arise from the fundus of the gallbladder. The state preceding spontaneous rupture has been termed “empyema necessitatis” by Nayman. This term essentially describes a “burrowing abscess” of the abdominal wall as a result of gallbladder inflammation.

Based on the underlying aetiology, the external biliary fistula management differs. The acute phase requires treatment with adequate antibiotics, analgesia and resuscitation. Not all external biliary fistulas warrant surgical intervention because a proportion of patients exhibit spontaneous healing. So, in elderly or debilitated patients major interventions can be avoided. Possible surgical options include cholecystostomy with removal of the gallstones or cholecystectomy. Cholecystectomy is becoming the treatment of choice because cholecystostomy carries the risk of future stone formation in the gallbladder [6].

Conclusion

Gallstones-disease related complications can be prevented by early laparoscopic cholecystectomy. In patients with anterior abdominal wall discharging sinus should warrant early referrals. Rare possibility of malignancy should be kept in mind while dealing with spontaneous CCF. In these cases, proper preoperative planning with imaging like CT scan is pivotal. At last, the choice of laparoscopic versus open and one-stage versus two-stage approach should be guided by the patient’s clinical condition, local expertise and the best post-operative outcome for the patient.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of the patient’s clinical details and related images.

Learning points

• Chronic cholelithiasis related complications can be prevented by early laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

• In patients with anterior abdominal wall discharging sinus should warrant early referrals.

• Rare possibility of malignancy should be kept in mind while dealing with spontaneous CCF

• Proper preoperative planning with judicious use of CT imaging is pivotal to rule out the diagnosis and to plan for the definitive procedure.

References

- Crespi M, Montecamozzo G, Foschi D (2016) Diagnosis and treatment of biliary fistulas in the laparoscopic era. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2016: 6293538.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Puestow CB (1942) Spontaneous internal biliary fistulae. Ann Surg 115: 1043-1054.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Dadoukis J, Prousalidis J, Botsios D, Tzartinoglou E, Apostolidis S, et al. (1998) External biliary fistula. HPB Surg 10: 375-377.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Yuceyar S, Erturk S, Karabicak I, Onur E, Aydogan F (2005) Spontaneous cholecystocutaneous fistula presenting with an abscess containing multiple gallstones: A case report. Mt Sinai J Med 72: 402-404.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Hoffman L, Beaton H, Wantz G (1982) Spontaneous cholecystocutaneous fistula: A complication of neglected biliary tract disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 30: 632-634.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

- Vasanth A, Siddiqui A, O'Donnell K (2004) Spontaneous cholecystocutaneous fistula. South Med J 97:183-185.

[Crossref], [Google Scholar], [Indexed]

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences