A Rare Case of Spontaneous Splenic Rupture Post Acute Pancreatitis in Pediatrics: A Case Report

Abstract

A 10-year-old girl with an OCLN gene mutation and multiple co-morbidities. The patient has been admitted in the pediatric long term and complex care unit for most of their life and experienced acute pancreatitis during the stay in pediatric long term care unit. Two weeks after the pancreatitis diagnosis, the patient developed symptoms indicating internal bleeding. A Computed Tomography (CT) angiogram reported a large splenic hematoma with a moderate amount of free fluid in the upper abdomen and pelvis. These findings, when correlated with the clinical and laboratory findings were thought to represent rupture of the spleen. The patient was then managed conservatively as there was no further deterioration in the clinical situation. This case highlights the rarity of spontaneous splenic rupture in pediatric patients with pancreatitis.

Keywords

Pancreatitis; Splenic hematoma; Atraumatic splenic rupture; Spleen, angiography; Ultrasound

Introduction

Splenic rupture in the absence of trauma is uncommon but potentially life threatening. It can occur in the setting of infections, malignancies or inflammation conditions such as pancreatitis. While there has been an increasing number of case reports of splenic rupture post pancreatitis in adults, pediatric cases remain undocumented. Initially, with the pediatric population and subsequently in the adult population, nonoperative observation became more prevalent for hemodynamically stable patients [1]. This case report presents a rare case of atraumatic splenic rupture in a child with acute pancreatitis, managed conservatively due to clinical stability.

Case Presentation

Patient background

A 10-year-old girl with an OCLN gene mutation and multiple co-morbidities, including a seizure disorder managed with antiepileptic drugs (Clonazepam and Levetiracetam), global developmental delay, microcephaly and congenital intracranial calcification secondary to occludin enzyme deficiency. The patient also has a gallbladder stone, swallowing dysfunction, severe reflux, chronic kidney disease (stage 2), chronic respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation and was fed via a gastrojejunal tube.

Clinical presentation and laboratory results

During the stay in pediatric long term unit, the patient developed acute pancreatitis presenting with vomiting, irritability and abdominal tenderness. Laboratory results showed white blood cells ( WBC 18.4 × 103/ μL, neutrophils 82.5%), Hemoglobin (HB 15.8 g/dL), C-Reactive Protein (CRP 100.9 mg/L) and high level of pancreatic enzymes (lipase >3000 U/L, amylase 79 U/L) along with elevated renal function markers (serum creatinine 121 μmol/L urea, 9.5 mmol/L) and normal serum electrolyte and coagulation profile.

Imaging reports and initial management

A Contrast Enhanced Computed Tomography scan (CECT) revealed acute pancreatitis with secondary peritonitis and additional reactionary gallbladder distension. An abdominal ultrasound showed a 6 mm gallbladder calculus without sonographic features of acute cholecystitis.

The patient was managed conservatively by keeping the NPO (Nil Per Os) with intravenous fluid hydration and was treated with pain killers (paracetamol and morphine IV), antiemetics (ondansetron IV) and antibiotics (piperacillin-tazobactam). Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN) was initiated through PICC (Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter) on day 8 of the illness. Gradual jejunal feeding was started and full jejunal feeding was only reached for one day then it stopped due to frequent vomiting, so TPN was continued for 10 days.

Clinical progress

Clinically, the patient started to improve within one week. Inflammatory markers and pancreatic functions appeared to improve (Lipase 59 U/L Amylase <3 U/L on day 13 from diagnosis). One week after PICC insertion in the right arm, thrombophlebitis was confirmed by doppler ultrasound so the PICC was removed and started on a therapeutic dose of anticoagulation therapy which was later discontinued due to the splenic hematoma. A new PICC was inserted in the left arm, but also complicated by thrombophlebitis one week post insertion, so it was removed and a central line port-a-cath was inserted.

On day 15 of illness, the patient became lethargic and irritable with a picture of sepsis and laboratory tests showed a significant rise in the inflammatory markers (WBC 33 × 103/uL, platelet 626 × 103/uL CRP 317 mg/L) and acute on top of chronic kidney injury. Despite treatment with antibiotics (meropenem and vancomycin), the patient’s condition deteriorated and became pale, irritable and tachycardic the next day. A CBC showed an acute drop in hemoglobin from 8 gm/dl to 4.4 gm/dL within 8 h, so urgent blood transfusion was done which raised the hemoglobin to 8.4 gm/dL.

Imaging findings

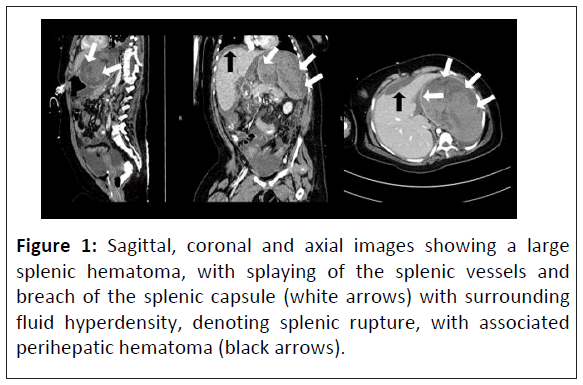

A follow up CT abdomen with contrast Figure1 reported a large hematoma occupying the splenic bed measuring 13.4 × 10 × 14 cm in craniocaudal, transverse and AP dimension respectively, without active extravasation (could represent splenic rupture/shattered spleen with big hematoma). The splenic artery is attenuated distally and intra splenic branches are not specified with contrast, same is noted in the splenic vein. Collection is seen in the sub hepatic region lateral to the stomach with enhancing wall measuring about 7 × 7.7 × 7 cm (Figure 1).

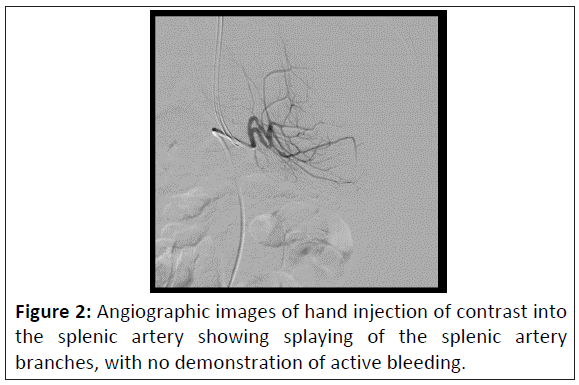

Conventional angiography was done showing splaying of the splenic artery branches, with no demonstration of active bleeding. But this did not preclude bleeding from arteries compressed by the significant hematoma around the spleen and the liver (Figure 2).

Management and outcome

The patient was managed conservatively with NPO (Nil Per Os) (Nothing by Mouth), IV fluids, antibiotics, tranexamic acid and blood transfusions (twice). There was no further hemoglobin drop or clinical deterioration. One week later, jejunal feeds were started gradually and increased till the patient reached full feeding. Hb rose to 10.8 g/dL. Follow-up abdomen CT with contrast after 6 weeks showed a significant reduction in volume and extension of intra-peri splenic collection, measuring about 9.2 × 11.3 × 8.4.

Discussion

Splenic rupture is usually caused by a blunt trauma but there are other non-traumatic causes which are quite rare such as hematological, infectious and oncological causes. Spontaneous rupture of a previously healthy spleen is extremely rare. However, there are cases in the literature which describe spontaneous splenic rupture in adult patients with acute pancreatitis [2]. It is a very rare but potentially life-threatening complication. The diagnosis of splenic rupture is challenging especially if a patient is not able to verbalize their symptoms or clinical complaints. Splenic complications are considered rare events during the course of acute and chronic pancreatitis and have varied descriptions, including pseudocyst, subcapsular hematoma, splenic infarction, intrasplenic hemorrhage and splenic rupture [3]. Although the pathophysiology of splenic complications is not completely understood, the close anatomical proximity between the spleen and the pancreas has been considered as a major contributor to splenic complications during pancreatitis. The splenic artery and vein and pancreatic tail, which are all located in the lienorenal ligament, enter the splenic hilum. This close anatomical association may lead to splenic involvement (e.g., intra-splenic abscess, pseudocyst formation, infarction, hemorrhage and rupture) with pancreatitis [4].

Vascular complications of acute pancreatitis result from the proteolytic effects of the pancreatic enzymes. The splenic artery, followed by the pancreaticoduodenal and gastroduodenal arteries, are affected most commonly. If acute hemorrhage is suspected or diagnosed by US or CECT, a celiac/superior mesenteric arteriogram should be performed to definitively assess the extent of vascular involvement [5]. CECT (Contrast Enhanced Computerized Tomography) scanning of the abdomen and pelvis is the standard imaging modality for evaluating acute pancreatitis and its complications [6]. Imaging protocols vary, but the most important unifying point is to obtain thin-section images during the peak of pancreatic arterial perfusion [7]. A contrast-enhanced CT scan should be obtained to determine the density difference between the splenic parenchyma and hematoma [8]. It may show disruption in the normal splenic parenchyma, surrounding hematoma, intraparenchymal hematoma and free intraabdominal blood.

Venous thrombosis can be identified through a failure of the peripancreatic vein (e.g., splenic vein, portal vein) to enhance or as an intraluminal filling defect [9]. Hemorrhage appears as highattenuation fluid collections. Active bleeding is seen as contrast extravasation [10,11].

Although splenectomy was the traditional management of spontaneous splenic rupture, numerous recent reports have documented positive outcomes with non-operative management, so this treatment modality is increasingly evolving. Nonoperative management can be successful in hemo-dynamically stable patients and in most cases reported, arterial embolization and percutaneous drainage were effective for treatment. The most important precondition for successful selective nonoperative management is adequate patient selection.

Conclusion

Atraumatic splenic rupture is a rare complication of pancreatitis, but potentially life-threatening complication. However, the number of described ruptures in the setting of acute pancreatitis has been growing. CECT scanning of the abdomen and pelvis is the standard imaging modality for evaluating the splenic rupture and acute pancreatitis complications. Treatment predominantly depends on the patient’s hemodynamic stability and clinical assessment. Starting with the pediatric population and expanding into the adult population, non-operative observation became more prevalent for hemodynamically stable patients.

The hemodynamically unstable patient with splenic rupture or hemoperitoneum will require emergency surgical intervention, in hemodynamically stable patients, splenic artery embolization, percutaneous collection drainage and conservative approach can be considered. Splenic complications should be ruled out in any patients with acute abdominal pain who were known to have acute pancreatitis in the recent past.

Key Clinical Message

Spontaneous splenic rupture after pancreatitis has been reported in adults but to the best of our knowledge and from the literature review conducted, there are no previous reported cases of spontaneous splenic rupture in children.

References

- Bjerke HS, Bjerke JS (2009) Splenic rupture. Medscape.

- Pai D, Aslanyan A (2015) Splenic rupture as complication of acute pancreatitis. Eurorad 12890.

- Hernani BL, Silva PC, Nishio RT, Mateus HC, Assef JC (2015) Acute pancreatitis complicated with splenic rupture: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 7: 219.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Fishman EK, Soyer P, Bliss DF, Bluemke DA, Devine N (1995) Splenic involvement in pancreatitis: Spectrum of CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 164: 631-635.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Jain D, Lee B, Rajala M (2020) Atraumatic splenic hemorrhage as a rare complication of pancreatitis: Case report and literature review. Clin Endosc 53: 311-320.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Romero-Urquhart GL, Karani J (2022) Acute pancreatitis imaging.

- Hirota M, Satoh K, Kikuta K, Masamune A, Kume K, et al. (2012) Early detection of low enhanced pancreatic parenchyma by contrast-enhanced computed tomography predicts poor prognosis of patients with acute pancreatitis. Pancreas 41: 1099-1104.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Banday IA, Gattoo I, Khan AM, Javeed J, Gupta G, et al. (2015) Modified computed tomography severity index for evaluation of acute pancreatitis and its correlation with clinical outcome: A tertiary care hospital based observational study. J Clin Diagn Res 9: TC01-TC05.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Tonolini M, Ierardi AM, Carrafiello G (2016) Atraumatic splenic rupture, an underrated cause of acute abdomen. Insights Imaging 7: 641-646.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Balthazar EJ, Robinson DL, Megibow AJ, Ranson JH (1990) Acute pancreatitis: Value of CT in establishing prognosis. Radiology 174: 331-336.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Ljubicic L, Sesa V, Cukovic-Cavka S, Romic I, Petrovic I (2022) Association of atraumatic splenic rupture and acute pancreatitis: Case report with literature review. Case Rep Surg 2022: 8743118.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences